Producers are receiving no help from public policy, unlike rice farmers

©Bloomberg

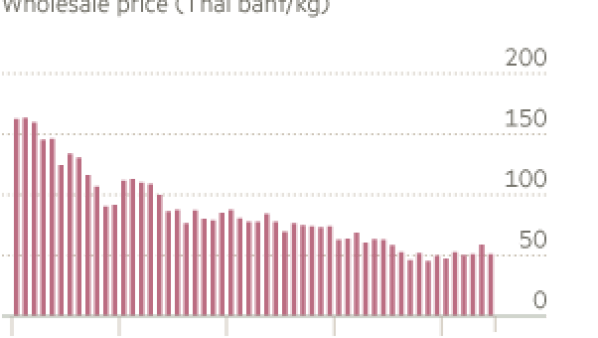

©BloombergAt a time when little is going right for Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy, and after a decade of debilitating political instability, Thailand is being hit hard by weak global demand for its major agricultural exports. Among the people most affected are the country’s rubber producers, suffering depressed prices since January 2014.After surging to more than 160 baht ($4.65) a kilogramme in early 2011, the local price of wholesale sheet rubber fluctuated between 80 and 100 baht/kg until the end of 2013. Then came the crash. By early 2014, prices had fallen to around 60 baht/kg, well below the point that farmers consider worthwhile, and have not yet recovered.

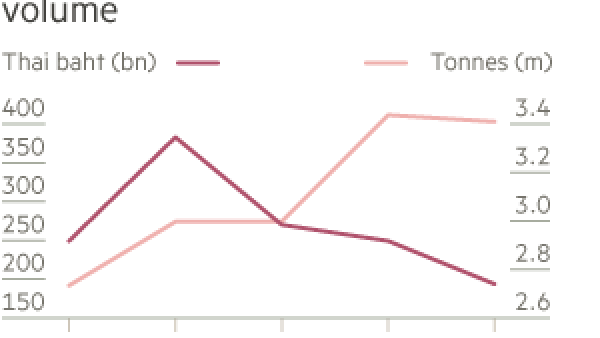

Thailand is the world’s largest producer and exporter of natural rubber; rubber exports accounted for 1.6 per cent of gross domestic product in 2014, down from 3.6 per cent in 2011 and 2.4 per cent in 2012.

According to research by FT Confidential Research, including trips to southern Thailand’s three largest cities and interviews with local industry organisations and chambers of commerce, the attractive price of rubber from 2010 to 2013 led many farmers to expand operations and plant rubber trees in place of other crops. As a result, the volume of Thailand’s rubber exports grew 15 per cent year-on-year in 2013, and held steady in 2014, even as prices tumbled.

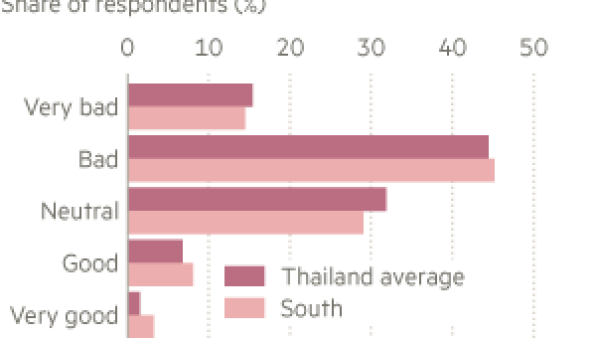

Unlike Thailand’s rice growers, who are insulated from global prices by a stable domestic market that absorbs about half their output, rubber farmers depend almost entirely on volatile export markets. Neither the Puea Thai government of 2011–14 nor the military junta that took power in the May 2014 coup has done much to help. Southerners generally expected this from Puea Thai, which received little support from the south, but many believed the military would take action.

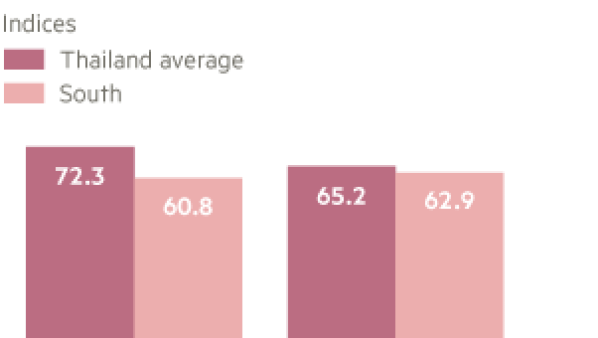

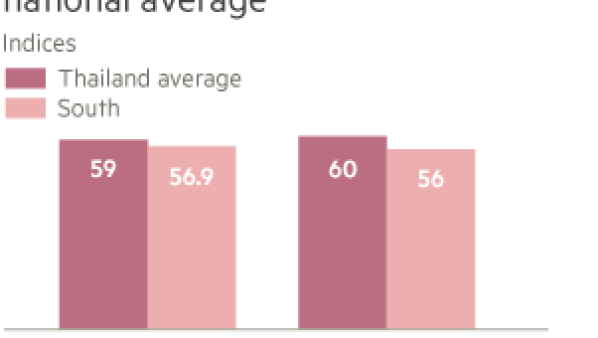

Surveys by FTCR show that respondents in southern Thailand hold negative views of economic conditions compared with their counterparts in the rest of the country.

Rubber farmers are a vital part of the economy in southern Thailand. They are land owners, businessmen and a vital source of employment for seasonal labourers. As with rice growers further north, they drive a large part of consumer spending in many areas.

FTCR survey data suggest that southern households have experienced less income growth in the past year than those in the rest of Thailand. Yet southern respondents also report increased discretionary spending and increased borrowing, at about the same rate as other Thai consumers — suggesting that Thailand’s household debt addiction is at least as much a problem in the south as it is elsewhere.

During research trips to Hat Yai, Nakhon Si Thammarat and Surat Thani, FTCR found that car dealers had experienced a greater slowdown in purchases than dealers elsewhere in the country (nearly all of which have seen a large drop in sales following the 2012 first car tax rebate scheme). Some were hit by year-on-year declines of as much as 70 per cent, and all reported rising numbers of consumers who had made deposits but failed to qualify for financing, most often for excessive debt-to-income levels.

One way Thailand could shield its rubber producers from volatility in global prices — and increase its footprint in a major global industry — would be to champion a domestic tyre industry. Although it leads the globe in natural rubber and produces more than 2m cars a year, Thailand exports almost 90 per cent of its rubber, mostly to tyremakers in China and India. The government would be wise to encourage investment by global tyremakers, perhaps in a planned special economic zone in Songkhla province, on the country’s southern border with Malaysia.