January 26, 2016 Updated 1/26/2016

Email Print

Ellen MacArthur Foundation Ellen MacArthur discusses a new study on the extent of plastics pollution.

Washington — A new report claims that by the middle of this century there will more plastic than fish, by weight, in the world’s oceans. But from the plastics industry perspective, it’s really revenue swimming away.

The World Economic Forum/Ellen MacArthur Foundation study, “The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics,” released at WEF’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, says that while delivering many benefits, “the current plastics economy has drawbacks that are becoming more apparent by the day.”

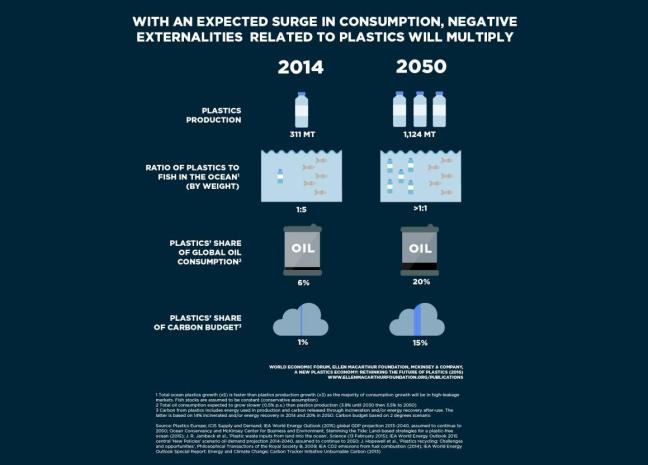

The report’s projections estimate that “by 2050 oceans are expected to contain more plastics than fish [by weight], and the entire plastics industry will consume 20 percent of total oil production and 15 percent of the annual carbon budget. In this context, an opportunity beckons for the plastics value chain to deliver better system-wide economic and environmental outcomes, while continuing to harness the benefits of plastic packaging.”

The 118-page report claims that 95 percent of plastic packaging — worth between $ 80 and $ 120 billion — is lost to the economy every year.

“A staggering 32 percent of plastic packaging escapes collection systems,” it says, “generating significant economic costs by reducing the productivity of vital natural systems such as the ocean and clogging urban infrastructure.”

Plastic packaging heavy hitters, from Unilever and Coca-Cola to Nestle and Sealed Air, were part of the study, as well as scores of academics, environmentalists and waste management experts. But the growing peril of marine plastics is hardly news to anyone in the plastics industry, especially on the packaging side.

The American Chemistry Council noted in a Jan. 19 statement that the U.S. plastics industry already is working to increase recycling — with 6 billion pounds recycled annually now — and recover energy from plastics that cannot be easily recycled.

“Plastics makers actively support programs designed to dramatically increase plastics recycling, especially for newer categories such as rigid plastics and film,” ACC said, citing the international Declaration for Solutions on Marine Litter, a 2011 manifesto signed by more than 60 plastics industry-related associations in 34 countries that has helped launch more than 185 projects addressing marine litter, as an effort to do something about the problem.

“If anyone hates seeing these materials wasted, it’s the plastics industry, and conversely, no industry wants to see these materials put to their highest, best use more than we do,” said Patty Long, senior vice president of industry affairs at the Washington-based Society of the Plastics Industry Inc. “That’s why SPI is engaging the entire plastics supply chain to find, develop and implement market-driven solutions to the collection challenges that prevent plastic materials from having more than one life, whether that’s through recycling, energy conversion or any other technology that derives value from plastics that would otherwise become litter or landfill fodder.

“We look forward to working with world policymakers and thought leaders to move toward a world in which none of these valuable materials are ever wasted,” she said.

Solving the problem

Ellen MacArthur Foundation The study notes that most of the waste is coming from developing regions in Asia.

While such hand-wringing studies as the latest from WEF/Ellen MacArthur Foundation sometimes seem to present a desperate problem with rigid and prohibitively expensive solutions, there are plenty of small-scale projects popping up around North America and the world with the potential to stem the tide of the ocean’s plastics problem — and the plastics industry’s losses — with government help.

Cited in the report as an example of a successful program in which industry and governments are working together to recover and recycle plastics in order to keep materials out of the environment, is Multi-Material BC (MMBC), a non-profit organization fully financed by industry to manage residential packaging and printed paper recycling programs in Canada’s British Columbia province.

Though it was the first government in the world to establish a container deposit and recycling system, British Columbia has spent two years reimagining a legacy recovery and recycling system designed for paper, glass, tin and aluminum and better equipping it for plastics, said MMBC Managing Director Allen Langdon. Sorting all containers in one central, high-performing facility rather than investing to retrofit four or five traditional material recovery facilities has saved the province money as well as enabled MMBC to drive efficiencies and start using the 2-year-old system as a platform to engage producers in real-time trials and studies to test packaging innovations.

“What we’ve done is not just the right decision for today but right for 10 years from now,” Langdon said.

“It’s a total paradigm shift from looking at it as a bunch of individual operations to looking at the entire stream it as an entire system,” he said. “But because we now have oversight over the entire system, we can make more rational decisions at every stage.”

Plastic film has been a particular success, he said. It used to end up in mixed bales and be sent overseas, “now we’re able to recycle it reasonably in North America. And a clean stream means a better price, too.”

Now that the paradigm shift has been made, and industry is being dealt in on decision-making and development, the model could be portable, Langdon said.

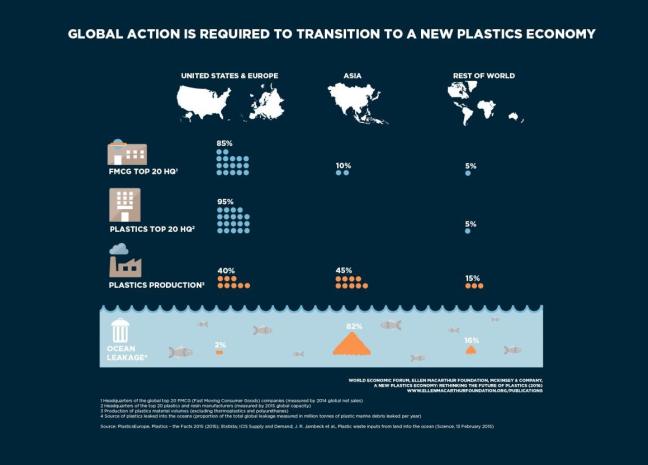

According to the report, 80 percent of the plastic “leakage” into the oceans is coming from developing countries, particularly in Asia. As overall consumption in developing nations grows, the plastic product and packaging implications seem almost overwhelming — unless it’s viewed by the industry and local governments as an opportunity.

“There are opportunities where there aren’t systems in place already, in developing countries, for them to make a wholesale leap forward and go beyond some of the struggles of the developed world,” Langdon said.

Sister publication PRW contributed to this report.