HAT YAI, Thailand — Plunging rubber prices have driven Thailand’s 6 million natural-rubber growers into a corner.

With rubber traded at prices one-fifth of their peak, the Thai government has introduced measures aimed at helping growers get out of the hole, such as high-priced purchases. But the measures are widely expected to fall well short of reviving the industry in the world’s largest rubber producer, mainly because they will only serve to maintain the glut intact.

Songkhla in southern Thailand is one of the leading rubber producing provinces that have been hit hardest.

Nam Yang Tai Cooperatives Ltd. in Hat Yai district sells rubber on behalf of local growers. Thanayospan Mektrong, president of the cooperative, begins his work day by negotiating prices over the phone.

“I let manufacturing plants compete in order to sell rubber at high prices,” he said.

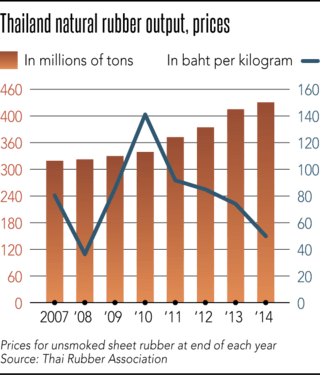

On the day I visited, negotiations started at 33 baht (94 cents) per kilogram of latex. Several calls and anxious exchanges later, Thanayospan had managed to haggle up to 35 baht, but a difference of 2 baht means little to growers. Prices were as high as 180 baht in early 2011 and have since fallen to a seven-year low.

The cost of producing rubber sheets can be 64 baht per kilogram, depending on the size and efficiency of the plantation, said Kititat, deputy manager at the Rattaphum cooperatives in the district adjacent to Hat Yai.

With prices below cost and unsustainable, in January the government began buying rubber sheets at 45 baht per kilogram (42 baht for latex) with a ceiling of 100,000 tons.

At a rubber-trading facility in Rattaphum, 66-year-old plantation owner Prapan Maneesawang had brought latex gathered in the morning.

The milky-white sap is mixed with acid and solidified into a sheet, which is called an unsmoked sheet, or USS. Once dried in a smoking room, a USS becomes a ribbed smoked sheet, an RSS, which can also be traded.

Only latex of a certain density is eligible for the government scheme, which effectively inflates the market price by 35%. The latex brought by Prapan did not meet the requirement and fetched just 31 baht per kilogram.

The rescue program only helps growers to a limited extent, he said, claiming that the government’s purchase prices are not sufficient as they are lower than 60 baht demanded by growers.

Despite failing to meet the requisite density, Prapan is in a better position than many other growers. He reinvested profits when rubber prices soared five years ago and expanded his plantation from 9 rai (14,400 sq. meters) to 70 rai, meaning he can still earn enough, despite plunging prices.

A worker engages in shipping work at a facility of the Rubber Authority of Thailand in Rattaphum on Feb. 9.

Many other growers in the neighborhood are in an altogether different situation. They enjoyed the good times, buying new cars on bank loans as local branches sprung up across the region, recalled Chot Thongiead, district chief the Rubber Authority of Thailand.

Now that the prices have plunged, most of the Mercedes and BMWs have been repossessed.

Montchai Pinitjitsamut, professor of economics at Kasetsart University, has proposed establishing a bailout fund, envisaging that rubber growers contribute to a pool of funds when prices are high and receive financial support from it when prices fall. The safety mechanism was proposed to the government but no action has been taken.

The drop in prices comes off the back of increased competition with synthetic rubber amid falls in crude oil prices and the economic slowdown in China, a leading buyer. But many say Thai growers only have themselves to blame for their current plight.

Workers process latex brought to a purchasing facility in Rattaphum on Feb. 9.

The history of Thailand’s natural rubber industry has seen one production hike after another in recent years.

The country overtook Malaysia and Indonesia in around 1990 to become the world’s biggest producer and has kept boosting production for a quarter of a century. Rubber output in 2014 logged a 2.7-fold increase on 1990, according to the Thai Rubber Association.

Even as prices began to go south in 2011, Thai growers continued to increase production, completely throwing off the supply-demand balance.

In a bid to realign the balance, the government uses rubber it buys at inflated prices for infrastructure projects, for example extending the durability of road surfaces. Rubber can be also used to produce artificial turf for sports facilities.

But as the government has capped its purchase at 100,000 tons, the bailout program is expected to last until June at the latest.

Experts point out that the Thai rubber industry is in a weak position because nearly 90% of its output is exported after very little processing. The country has few end users that produce value-added rubber products like Malaysia’s Top Glove, the world’s largest manufacturer of natural rubber gloves.

Belatedly, the government has sought to address the problem.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha and Deputy Prime Minister Somkid Jatusripitak, who heads up the country’s economic affairs, made an inspection tour of an industrial park near Hat Yai late last year, where they were greeted by a large new signboard reading “Rubber City.”

Workers at the local cooperative ship rubber sheets in Rattaphum on Feb. 9.

The project is aimed at luring rubber-product manufacturers to the center of the rubber producing region in order to raise demand in Thailand. The government will create the park on 750 rai or, 12,000 sq. kilometers, of land and offer tax breaks as well as other incentives to attract businesses.

Foreign companies, including many from China, have already shown interest, said people involved in the project.

Whether or not Rubber City becomes commercially viable remains to be seen, but it is unrealistic to think the project can single-handedly turn the Thai natural rubber industry around.

The basic problem is that there are simply too many rubber trees in Thailand, and the excess needs to be replaced with other crops from which farmers can earn a sustainable living.

Global markets now wait anxiously to see whether the world’s largest natural rubber producer can carry out badly needed structural reforms and put the industry back on its feet.