Agricultural companies are expanding their rubber businesses even after prices of the commodity plunged recently to nearly seven-year lows

While depressed rubber prices are making it hard for smallholding farmers to eke out a living, big agricultural businesses are creating large plantations across Southeast Asia, partially reversing decades of downsizing in the sector.

A worker collecting latex from a rubber tree at a plantation in Pahang, Malaysia, on Jan. 12. PHOTO: AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

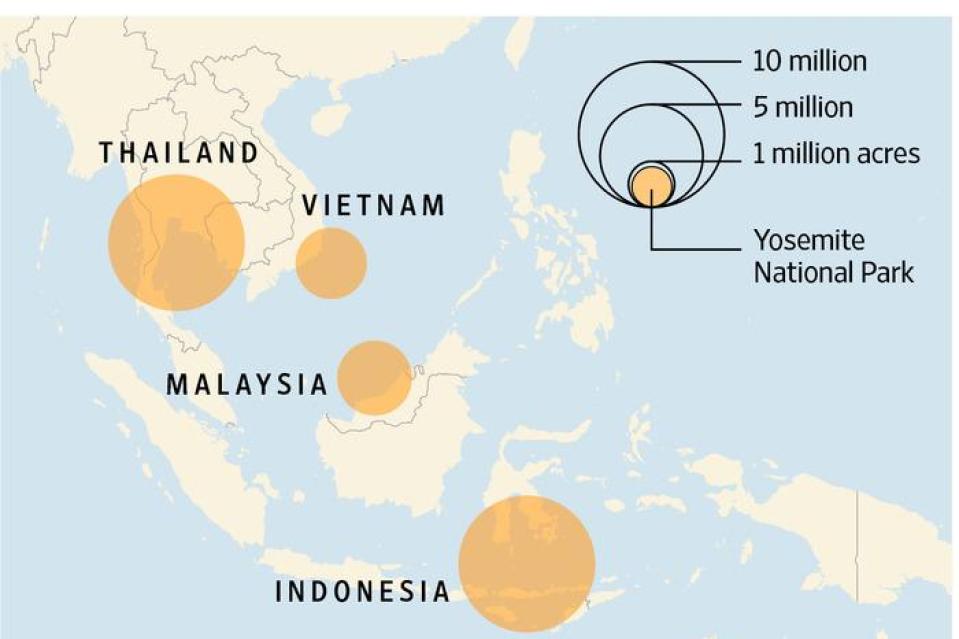

In Malaysia, one of the world’s top three rubber exporters, acreage owned by large estates dedicated to rubber increased 7.5% in 2015, while small-farmer holdings rose less than 1%, according to the Malaysian Rubber Board. In Indonesia, another top exporter, rubber plantations owned by large estates rose 2.5% in 2014, latest available government data show.

Among big Asian companies, Thai giant Sri Trang Agro-Industry PCL is finishing a plan started in 2009 to plant rubber trees on 20,262 acres of land.

Malaysia’s Sime Darby Bhd., one of the world’s largest palm-oil producers, plans to increase the share of rubber plantations in its agricultural-land portfolio to 10% from 2% over the next 10 to 15 years.

The renewed appetite for rubber plantations comes amid a prolonged slump in prices of the commodity used to make items from tires to latex gloves. Rubber prices hit their lowest level since 2009 earlier this year, as significant stockpiles and falling demand from China kept prices under pressure.

Yet large estates buying up rubber plantations are looking for long-term investment. The growth in large plantations in Vietnam has contributed to the current oversupply in the market, however, and further increases could put more pressure on prices.

“Growth in plantations can be good for small holders if it is inclusive and provides them with technical assistance and a reliable return,” said WWF International Forests DirectorRod Taylor. “It can be bad if it pushes them out and makes it harder for them to compete.”

The recent trend of larger plantations comes after several decades during which the role of big players in Southeast Asia diminished as more land was given over to producing palm oil. In 1965, around 40% of rubber production in Malaysia, the then largest producer, came from large estates, according to the Department of Statistics Malaysia. Last year, they accounted for just 8%, according to the Malaysia Rubber Board.

The commodity is produced by tapping into rubber trees and collecting and processing the liquid, known as latex, which drips out, a labor-intensive process that made it somewhat unattractive for large corporations.

The shift back to rubber now is due partly to a belief palm oil has become too dominant.

“We are so overdependent on oil palm,” said Nageeb Abdul Wahab, head of upstream Malaysia for Sime Darby Plantation. He said the company had replaced rubber trees with oil palms in the years until 2000 because returns were better, but that it now plans to return some areas to rubber after realizing that these were too dry for the new crops.

‘The increase in new plantings and replantings by some of the large estates is part of a business strategy in an expectation of future rubber shortages.’

—Prachaya Jumpasut, managing director of The Rubber Economist

Other agricultural companies like Sri Trang reckon they can gain an advantage by owning both rubber plantations and processing plants.

“We want to be a fully-integrated business as we believe that by having a rubber plantation you are more aware of the situation on the supply side such as the weather conditions,” a company spokeswoman said. “Also you know what price you are going to have to pay per kilo of raw material.”

Low rubber prices are encouraging potential land buyers, too.

“Vendor expectations were very high three or four years ago and now that we’ve returned to more normal levels, you can buy in at a more acceptable level,” said David Brand, chief executive of Australia-based New Forests Asset Management Pty. Ltd., which has 2.8 billion Australian dollars (US$2.11 billion) of assets under management.

It is also an attractive investment for them because of the range of uses of rubber trees, implying there is profit to be made in the long term. Once trees mature and yields moderate, they can be felled and the hardwood timber sold as building material or to make furniture, Mr. Brand said.

The fund, partly-owned by Japanese trading firm Mitsui & Co., purchased a 35% stake in PT Hutan Ketapang Industri in February, which manages a 247,476-acre plantation forestry concession in Indonesia. It plans to triple its rubber plantation to 74,132 acres over the next six years.

“The increase in new plantings and replantings by some of the large estates is part of a business strategy in an expectation of future rubber shortages,” as low rubber prices are increasing the likelihood of small holders moving into other crops that give better returns or quitting farming, said Prachaya Jumpasut, managing director of London-based The Rubber Economist.