September 14, 2016 Updated 9/14/2016

Email Print

Bill Wood

Over the past few months, there has been something of a mini-surge in the data that measure U.S. output of computers and peripheral equipment. This comes after a sharp decline at the end of last year and a sluggish performance in the first quarter of 2016.

According to the Federal Reserve Board, the latest industrial production index figure for this industry came in at 106.3 (the average month in 2012=100). This marked the third consecutive month that the data was above 105.

If this trend continues, then the current quarter will post the strongest level of U.S. output of computer equipment in the past seven years. Unless the data is revised downward or this trend comes to an abrupt halt, I expect output of computer products will be flat for 2016 as a whole when compared with 2015. But they will end this year with good momentum, and moderate growth should emerge in 2017.

Now if I sound a bit cautious with this analysis it is because I am. One thing we have all learned over the last seven years is that just when is seems that the economy has turned the corner, and the growth rates for the major plastics end-markets will finally start to accelerate, well, it fizzles out and the data regress back to the prevailing trend of sluggish growth. Therefore, one just cannot get too excited about trends that emerge for only a quarter or two.

But if we allow ourselves to take a long-term perspective, then I think we can all agree that this is a crucial industry for the United States, and it should also be a vibrant end-market for plastics products. I believe strongly that this is how we will describe the computer industry 10 years from now.

But as far as the next two years are concerned, I am not so sanguine.

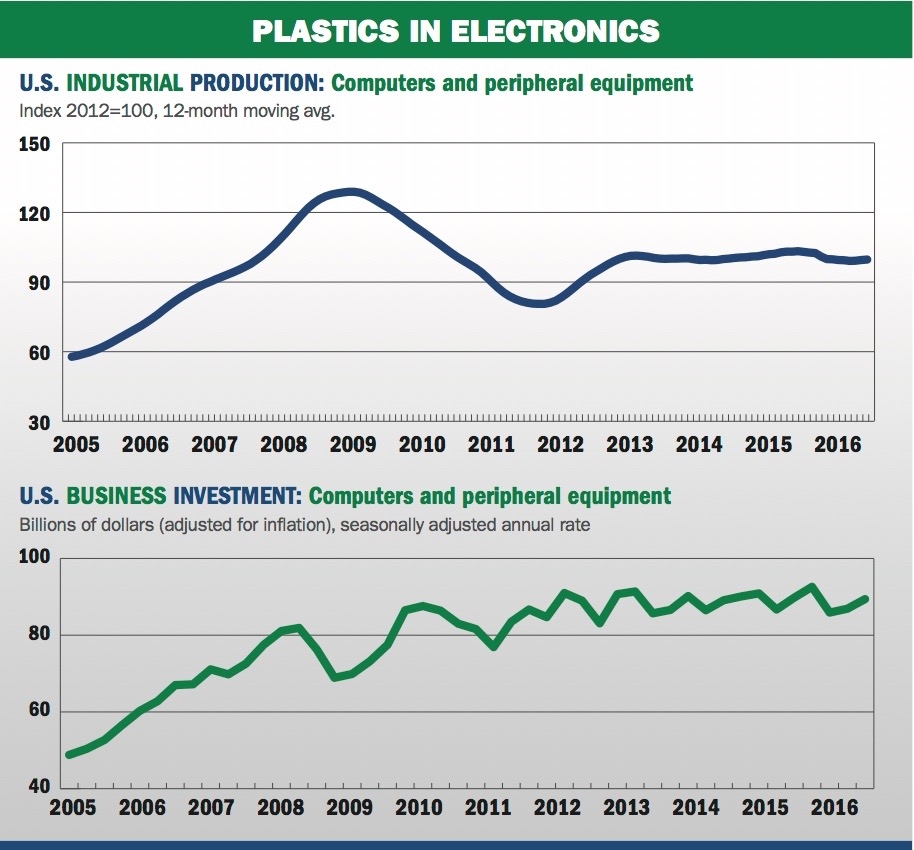

To aid in my explanation of my near-term skepticism, I have included two historical charts for your consideration: one is a graph of the 12-month moving average of the Fed’s index that I mentioned above; the other is a graph of the amount of business investment in computers and peripheral equipment that is compiled and reported every quarter by the Bureau of Economic Analysis as part of their report on U.S. GDP. I am using a moving average of the Fed’s data because it smoothes out any monthly noise or unmeasured seasonality in the data. I just want to capture the underlying trend.

Why the plateau?

What is immediately obvious from these two charts is that both the production levels and investment levels for computers have been flat for the past four years. This is surprising to me. The economy has been in a recovery for the past seven years. The growth rate has been slower than we want it to be, but it still qualifies as a recovery. During this time, interest rates have been at historic lows, profit levels for most corporate sectors have been at cyclical highs, and the labor market has improved substantially.

And yet, the data from the computer industry is flat. One theory for the plateau is that the production of these products has migrated to other countries. I believe this is one of the long-term issues in this industry, but that does not explain why domestic companies are not increasing their investment in these products, regardless of where they are manufactured.

This reticence to accelerate investment in computer equipment is a symptom of a bigger issue at the present time, and this is not the only end-market for plastics products that is affected. Companies’ desire to invest in new plants, equipment and employees is based on their rational expectations for future return on that investment. The return they get ultimately depends on the amount that consumers spend on all types of goods and services.

But the amount consumers spend is rationally based on their expectations for future wages or income, and that ultimately depends on hiring and investment by companies. Each side of this relationship seems to want more assurance that the other side is going to follow through with its plans. These intermittent fits and starts in certain sectors of the economy for brief periods of time are completely understandable in an economy that is grinding along at a sub-par rate of growth, but they are doing little to generate confidence in either business managers or consumers.

This chicken-or-egg dilemma started vexing economists and policymakers about the same time that the production and investment data started to hit a plateau, and argument about what to do about it persists to this day. By now you have no doubt heard the debate about whether the Fed should raise interest rates later this month. Some say it will hurt investment, and others say it will help it.

For my money, I do not believe that anything the Fed does this month will matter. Nor will Apple’s release of its new iPhone. And I do not believe that the election of either Donald or Hillary will matter much either (though I do believe that a strong showing by a third party would do wonders for what ails Washington D.C.). The U.S. economy is enormous, and it was severely damaged by the last recession. It is slowly, but surely getting things worked out, but it will likely need a little more time.

Forecast: More slow growth

Here is my forecast for the computer industry and also for the trend in business investment in new plants and equipment. There will likely be another year or two of sub-par economic growth. It will take this long at the current pace for the housing sector to recover fully from the last meltdown. Once the housing sector is functioning normally, consumers will accelerate their spending patterns and the economy will start to expand more rapidly.

So if you are a plastics processor that supplies the computer industry, you have a little time to prepare. After that, this will likely be one of the fastest growing sectors in the economy, and you will have to be ready to invest in some new equipment if you want to keep up.