Low productivity, high labour costs and sub-par quality are holding Myanmar back from becoming a serious rubber producer, experts say. The nation’s rubber plantations produce at less than half the international production rate, and a rise in volume must be matched by improvements in product quality, says Hajime Kondo, manager of Bridgestone’s tyre materials advanced development department.

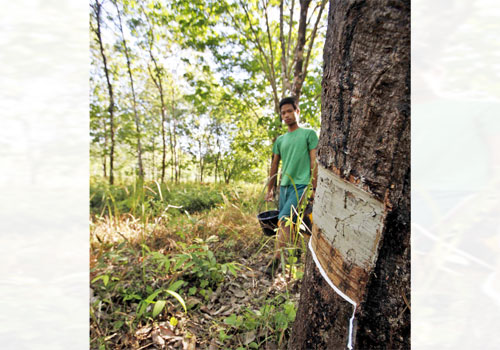

Natural rubber farm worker Win Latt collects milky white latex from a rubber plant in Dawei township in 2012. Photo: EPA

Natural rubber farm worker Win Latt collects milky white latex from a rubber plant in Dawei township in 2012. Photo: EPA

But growers complain that at current world rubber prices, they don’t earn enough income to pay a labour force increasingly attracted to job opportunities elsewhere, both in Myanmar and overseas.

“While other countries produce 1.5 tonnes of rubber per hectare, Myanmar produces 0.8 tonnes. And Myanmar is very different from other countries in terms of fixing rubber grading,” said Mr Kondo.

A recent seminar in Yangon Region on the sustainable natural rubber initiative (SNR-i) allowed industry professionals to share information about the natural rubber supply chain.

“Three years ago, Japan launched a project to support Myanmar natural rubber by improving the quality. A system of natural rubber laboratories was to be established with the goal of certifying quality to international standards,” said Mr Kondo.

“The training of lab staff is complete, and the equipment has been installed. Later this year, the International Rubber Association will certify the lab,” he said, adding that Japanese consumers had begun importing Myanmar rubber as its quality improved.

“Imports have increased a great deal over the past three years. Once the IRA certification is received,international consumers will be able to import Myanmar natural rubber more easily.”

As to the question of quality, some of the certified seeds used under the previous government were not very suitable for Myanmar’s geographical position, said U Aung Myint Htoo, president of the Myanmar Rubber Planters and Producers Association (MRPPA).

“Some regions and states are planting seeds inherited from other countries and not tested for some years. The previous agriculture ministry certified and registered those seeds, but the yield is not good,” he said.

“This question is not really related to the worldwide fall in rubber prices. If planters chose quality seeds, they could survive. Only a few small-scale rubber planters have quit the industry. That doesn’t mean Myanmar’s whole rubber industry is going to shut down,” he said.

Nevertheless, low prices do reduce the industry’s income, complicating efforts to improve quality, said U Aung Myint Htoo.

“Myanmar rubber exports go mostly to China. Japan wants to import, and we’ve been in negotiations with them, but will do so only if Myanmar can meet Japan’s quality demands. The Chinese import our rubber because of the lower price, and with that level of quality it’s hard to find another market,” he said.

Since hitting a spike about five years ago, rubber prices have declined from a high of nearly 280 US cents per pound to as low as 65 cents (Singapore Commodity Exchange (SICOM), prices quoted for No 3 Smoked Sheet, RSS3 standard). At the same time, the pool of farm labour has shrunk, growers say.

Smallholder U Kyaw Zwar, who owns the 20-acre (8-hectare) Sein Lan Pyae Sone rubber farm, said, “When we push labour harder to control quality, they leave for other farms, or go to Thailand. We only pay them about K3000 a day, so they can find other farmers who can pay more. In the year 2010, our rubber was earning K1850 a pound, but now we only get K700 a pound. We can’t afford to pay our workers more.”

The low price is compounded by the poor productivity, said MRPPA vice president U Myo Thant. “We could pay a third of our income to our labour force if we were growing 1500lbs an acre. But a farmer producing only 700lbs an acre cannot pay 500lbs’ worth of income to his workforce. It’s hard to improve rubber quality and get good labour as well,” he said.

Things may be slightly better for plantations operating on a larger scale. Some middle-range producers said most of the Chinese demand was for RSS3. None seem to plan to leave the industry.

U Nay Moe Myint, the owner of the 250-acre Cho plantation in Mawlamyine, Mon State, said low productivity was the result of low prices and slender export volumes.

“Chinese demand is pretty steady. Myanmar can’t produce much rubber, andsome small-scale growers have stopped production,” he said.

U Myo Aung, managing director of Yoma Top company, which exports natural rubber to Hong Kong and India, said local tyre companies were seeking to buy more rubber.

“We sell to the Yangon Tyre Company, and we’ve been getting a better price than if we’d exported. Japan has been trying to import Myanmar natural rubber, but they’re waiting for the quality to improve. They said if we met their quality standard, we could get the same price as other producers throughout the world,” he said.

More than 90 percent of Myanmar rubber is exported, mostly to China. But the higher prices being offered by local customers are a good sign, said U Myo Aung.

“I have a 1200-acre plantation in Bago that produced 100 metric tonnes of rubber last year. We estimate we will produce 140MT this year,” he said, attributing the increase to high-quality seeds.

According to the MRPPA, there are 734,436 acres (293,774ha) under cultivation, producing 227,533MT in the current year.