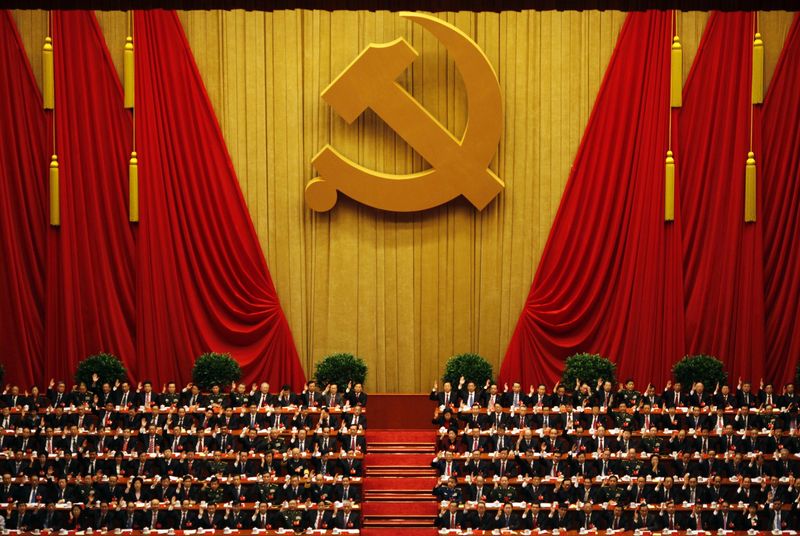

© Reuters. As China’s leaders gather, market reform hopes fade

© Reuters. As China’s leaders gather, market reform hopes fadeBy Michael Martina and Kevin Yao

BEIJING (Reuters) – President Xi Jinping’s rule in China has been marked by a muscular stance in many areas – from corruption to foreign policy – but investors and business leaders hoping that the nation’s most powerful leader in decades will drive market reforms are girding for disappointment.

As he gears up for his second term, hoped-for market liberalization is increasingly being viewed as secondary to Xi’s state-centered approach to economic policy and his focus on stability. The Communist Party Congress beginning on Wednesday in Beijing is expected to see Xi consolidate his power and is unlikely to see a change in his priorities.

“I don’t see market opening coming. It’s all about discipline and control,” said one senior China-based American executive, who declined to be identified.

China’s State Council Information Office referred questions on market reforms to the country’s economic planning agency, the National Development and Reform Commission, which did not respond to a faxed request for comment.

Some Chinese policy insiders said that they don’t expect any significant speeding up. “We will not rush on reforms. The pace of changes will not change dramatically,” said one advisor to the Chinese government who was speaking on condition of anonymity.

EARLY HOPES DASHED

Xi’s sweeping anti-corruption campaign and his move to personally take charge of economic policymaking had initially been seen by China analysts as early signs that he would use his consolidated power to push tough reforms through entrenched bureaucracies.

The party’s 2013 pledge under Xi’s then-new administration to let the market play a decisive role in the economy had also given hope to those pushing for reform.

But many analysts and business leaders now see Xi’s faith in markets as tenuous, and that 2013 reform pledge as a mere holdover from his predecessors.

A lack of follow-through over the past several years on repeated State Council vows to open markets to the world have left foreign businesses with “promise fatigue”, as the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China put it last month.

Those delays coincide with the passage of a raft of new national security and cyber security laws and regulations that China’s trading partners complain will put them at a disadvantage.

“For the past 20 or 30 years it was economic development at all costs, and I think we are seeing a new paradigm now where national security is dominant and economic issues are channeled through that lens,” said Jude Blanchette, who studies the party at The Conference Board’s China Center for Economics and Business in Beijing.

Blanchette said true market reforms in Xi’s second term would mean walking back much of the control he has fought to acquire, an unlikely prospect.

STABILITY WINS

Other painful reforms that many economists say are needed have also moved slowly under Xi. They include overhauling China’s debt-laden state sector, fixing the fiscal system to tackle local government debt, bringing in new property taxes to ward off housing bubbles, and allowing farmers to sell their land more freely.

Capital controls, including restrictions on some outbound investment deals, have helped stabilize the yuan, but at the cost of hampering China’s ambition to internationalize the currency.

Chinese reform advocates say the government has been avoiding potentially disruptive changes due to concerns over economic and social stability and resistance from vested interests, such as powerful state-run companies.

“If there are no such reforms, the conflicts will keep accumulating while risks will be even higher, which could destroy our prospects to move forward,” said Jia Kang, director of the China Academy of New Supply-Side Economics, a Beijing-based think tank.

In 2015, Xi espoused his own state-led “supply side structural reform” doctrine, an effort in part to tame an explosion of debt by cutting capacity in heavy industries, and reduce risk from bad bank loans.

While Xi can tout continued robust economic growth – the government had set a 2017 GDP growth target of around 6.5 percent but it now looks like it will be closer to 7 percent – it is still reliant on credit and investment as opposed to more sustainable consumption.

And expanded state control over the economy is at the center of key Xi initiatives, including the “Made in China 2025” plan, which funnels billions of dollars into robotics, semiconductors, and other industries deemed strategic.

Despite government talk this year about opening some restricted sectors to overseas investment, some foreign business groups express scepticism, even as U.S. President Donald Trump is expected to seek some concessions for American businesses during his planned visit to Beijing in early November.

“Until we see the equity cap lifted from 49 percent to 50 percent or higher with foreign banks, or until we see foreign insurance companies able to fully access the market, we’re just having the same conversation we had five years ago,” said Jacob Parker, vice president of China operations at the U.S.-China Business Council.

CREATING CHAMPIONS

Xi has also reasserted that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) should be the commanding heights of the economy.

Foreign experts on Chinese markets point to government efforts to merge state companies into even larger champions as proof of how the state’s vision of reform does not necessarily mean increased use of free markets.

In recent years, Beijing has required state firms to reassert their Communist Party committees’ hold on corporate decision-making. A 2015 blueprint for SOE reform made no mention of the 2013 pledge for the decisive role of the market.

One senior western diplomat in Beijing told Reuters it has become increasingly clear that the top priority for Xi remains strengthening the primacy of the party and stability.

“When further opening up comes into conflict with that priority, the argument for stability tends to win,” the diplomat said.

Source: Investing.com