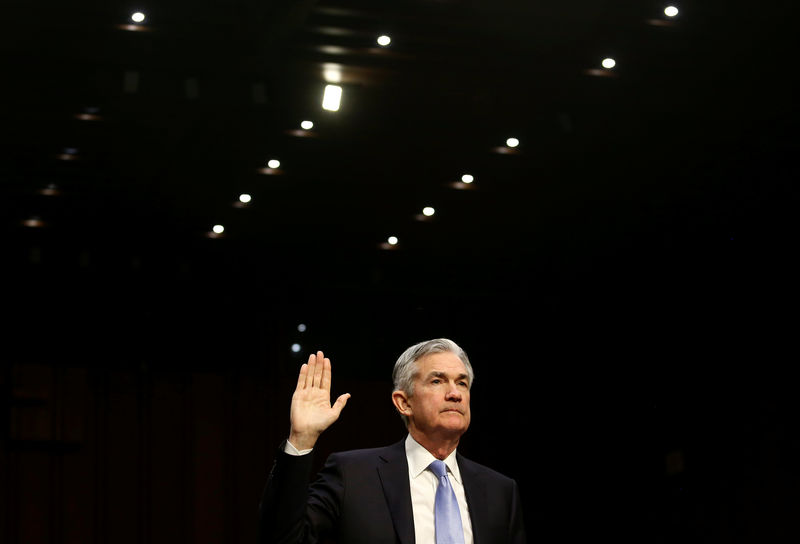

© Reuters. Jerome Powell testifies on his nomination to become chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve in Washington

© Reuters. Jerome Powell testifies on his nomination to become chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve in WashingtonBy Howard Schneider and Jason Lange

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Jerome Powell, President Donald Trump’s choice to lead the U.S. Federal Reserve, defended plans to potentially lighten regulation of the financial sector during a controversy-free hearing on his nomination to take over the central bank.

Tapped to replace current chair Janet Yellen, Powell on Tuesday skirted several efforts by members of the Senate Banking Committee to draw him into the debates preoccupying Capitol Hill, refusing to analyze the impact of proposed tax cuts or, as some of his colleagues at the Fed have done, argue for more immigration to boost the labor force. He said economic growth was likely bound in a range of between 2 and 2.5 percent annually, short of Trump’s 3 percent goal, without a jump in productivity that many economists regard as unlikely.

In general the 64-year-old lawyer stuck close to script, reciting the current Fed consensus that interest rates are due to continue rising gradually, that the course of inflation remains a mystery, and that weak wages and low labor force participation indicate the jobs market still has room to improve.

Early in his time as a governor Powell, a lawyer who has spent the bulk of his career in the private sector as an investment banker, shared some conservative concerns about the extent of the Fed’s crisis response. But he ultimately came to agree that the benefits of current Fed policy, with years of loose money allowing time for displaced workers to trickle back to the job market, outweighed the risks – and that future crisis would require the Fed, as he said in his opening statement, “to respond decisively.”

The sharpest and most detailed exchanges involved financial regulation, an area Powell has focused on during his years as a Fed governor and where he said it was time to take a pause and evaluate where things stand eight years after the end of a deep 2007 to 2009 recession.

“I am not characterizing what we are doing as deregulation…It is looking back and making sure what we did makes sense,” Powell told the committee. “It does not help anyone for banks to waste money.”

Powell said he wanted to be sure regulations were “tailored” to the size and role of different institutions, perhaps allowing smaller banks more latitude to trade securities and make other investments, and decreasing the frequency and intensity of “stress tests” for all but the largest financial companies.

In a statement that may surprise some analysts and regulatory experts, he declared the problem of banks that are “too big to fail” all but solved. Asked if any firms are still so large that their collapse would cause wide-ranging harm to the financial system, he responded “I would say no to that.”

Over the course of the roughly two-hour hearing none of the senators voiced opposition to Powell, though the back and forth over regulation prompted Democrats to question whether he would coddle Wall Street, while Republicans wondered if the Fed would go far enough in lightening the burden on financial businesses.

No Senate committee or floor vote has been scheduled yet, but Powell is expected to win confirmation before Yellen’s term expires in early February.

There was no obvious market reaction to Powell’s appearance in Congress. Analysts, meanwhile, noted the near-rote response to some questions and wondered what that portends when Powell – who would be the first non-economist to hold the top Fed job since the 1970s – confronts conditions that require him to improvise.

Trump nominated Powell from a list of five finalists that included Yellen, seeing in him a way to extend Fed policies that have driven unemployment to 4.1 percent and the stock market to record highs, but without having to renominate a veteran of prior Democratic administrations.

Powell’s hearing “contained few signs that he will bring any new thinking or a change of approach,” wrote Michael Pearce, U.S. economist for the Capital Economics consulting firm, referring to the nominee as “closely guarded” in his reiteration of existing Fed talking points. “We are increasingly worried that a policy mistake in either direction is possible in the years ahead.”

Compared to some other confirmation hearings in the Trump era, however, Powell’s was an almost congenial affair. During five years as a Fed governor, with deep ties to the region as a Maryland native and former Treasury Department official, he has built relationships with both Democrats and Republicans on the panel who said they respected his work.

Perhaps as a result, much of the questioning involved efforts to draw him out on issues like whether the tax plan being debated on Capitol Hill would – as Republicans argue – boost economic growth, or simply explode the debt as Democrats contend.

Powell dodged, resorting to a common Fed stance that tax and spending policy is up to elected leaders and outside the Fed’s authority.

“I am not an expert on what analysis is out there,” Powell said.

Source: Investing.com