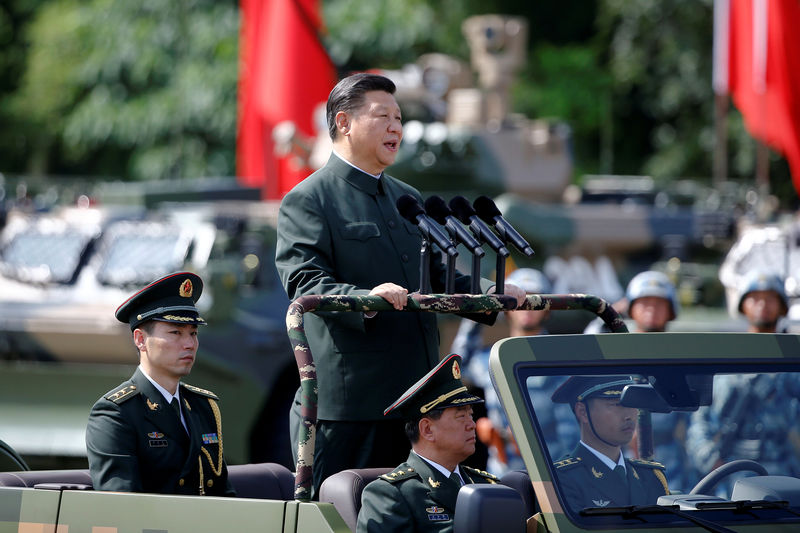

© Reuters. Chinese President Xi Jinping inspects troops at the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Hong Kong Garrison as part of events marking the 20th anniversary of the city’s handover from British to Chinese rule, in Hong Kong

© Reuters. Chinese President Xi Jinping inspects troops at the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Hong Kong Garrison as part of events marking the 20th anniversary of the city’s handover from British to Chinese rule, in Hong KongBy Greg Torode and Venus Wu

HONG KONG (Reuters) – As Hong Kong seeks more land to help ease a worsening housing crisis, some lawmakers and activists are urging officials to take a fresh look at little-used swathes of more than $100 billion worth of real estate controlled by the Chinese military.

The Hong Kong garrison of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) still occupies some 19 sites across the global financial hub it inherited from the British military when the former colony was handed back to China in 1997.

While several sites, such as the high-rise barracks near the Central financial district, are neon-lit and busy, others appear overgrown, rundown and little used, according to Reuters investigations, activists and diplomats monitoring military activity.

The parcels range from mansions in the exclusive Peak district and once-luxurious officers’ apartments in Hong Kong and Kowloon, to firing ranges and decades-old Nissen huts across the semi-rural New Territories, near the border with mainland China.

With Hong Kong property prices at record highs, Denis Ma, head of research at property consultancy JLL, said a mid-range estimate of the total land value could reach HK$1.06 trillion ($135 billion).

Based on the recent sale of a nearby plot, the Central site alone could be worth $29 billion and deliver 4.5 million square feet of floor space if developed into a commercial site.

Suitable residential land among the 19 sites could yield 65,000 family-sized apartments, Ma added.

Across Hong Kong, the PLA occupies some 2,700 hectares (6,670 acres), according to local government records, nearly half the size of Manhattan.

HOUSING PROBLEM

A lack of housing is a source of rising social and political tension in Hong Kong, one of the world’s most expensive property markets where owning even a 600-square foot flat is beyond the reach of many families.

A recently formed government task force on land supply acknowledged public calls for some military land to be returned for housing, but its chairman has said their development potential “may not be large”.

The task force’s initial meetings have instead advocated developing 1,400 hectares of new land through reclamation.

The preference for costly reclamation over re-purposing PLA land has led some to believe the Hong Kong government does not want to confront the Beijing leadership over a potentially sensitive issue of national security.

Under the laws that enshrine Hong Kong’s freedoms and autonomy, Beijing is given direct control of defense and foreign affairs.

Reuters sent questions to Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam, the government’s development bureau and the task force. In reply, a spokesman told Reuters the task force would consider ideas from the community, “their facts as well as their pros and cons”.

It would finalize its recommendations by the end of 2018.

“As far as we understand, all existing military sites in Hong Kong are currently used for defense purposes and none is left idle,” the spokesman said, quoting Hong Kong’s security bureau.

Lawmaker Eddie Chu, part of Hong Kong’s democratic opposition, said even though it was common sense to open up some military sites for housing, the local government would likely avoid asking tough questions of Beijing.

“The Hong Kong government must know this is a solution, but I expect them to pay lip service to it,” he said.

The PLA garrison and China’s Defence Ministry did not respond to faxed questions from Reuters.

WELL DEFENDED

Security experts say while some PLA presence is a fact of life, the city’s defense needs are easily met by Beijing’s rapidly modernizing forces – a vastly different situation to that faced by the British in defending their outpost during the Cold War.

“Hong Kong has never been so well defended … it is a tiny segment of the mainland and is surrounded by the now significant forces of the Southern Theatre Command of the PLA,” said Trevor Hollingsbee, a former Hong Kong security official and naval intelligence analyst with Britain’s Defence Ministry.

“Rather than serve a vital strategic interest, the PLA presence in Hong Kong is essentially to show the public who is boss.”

After inspecting the garrison as part of 20th handover anniversary celebrations in June, Chinese President Xi Jinping told the troops they were “an important embodiment to national sovereignty”, according to state media.

As well as its Central barracks, security experts and diplomats believe a naval base and small airfield are considered key local sites to the PLA, along with a Kowloon barracks that houses light tanks and anti-riot units.

Another 10-hectare Kowloon site and residential blocks near Shek Kong appear barely used, according to activists and Reuters’ own checks. Soldiers armed with rifles and bayonets guard the entrance to the Kowloon site, but some buildings appear dilapidated, others rundown and many are unoccupied.

At Shek Kong, the residential blocks appear little used, day or night, and security is lax. In camps closer to the border, small deployments of troops drill at dawn outside aging British-era huts and weed-choked fences.

The 122 hectares of the Stanley fort on Hong Kong’s prime southern coast is also underutilized, according to diplomats.

About half of the 8,000-10,000 soldiers of the Hong Kong garrison are based in the city at any time, security experts and diplomats believe. Key units are kept in southern China, along with its most advanced weaponry, including jet fighters and air defense weapons.

Chinese laws covering the garrison state that any unused land, after central government approval, should be handed back “without compensation” to the local authorities, so any deal would likely have no benefits for the PLA’s coffers.

Community organizer Sze Lai-shan, who assists some of the city’s 200,000 people living in wire cages and partitioned homes, said all options for the land should be on the table.”I think using some for temporary housing shouldn’t be a big issue,” Sze said. “We could perhaps use some existing buildings for temporary housing, or even build temporary housing on some sites.”

Source: Investing.com