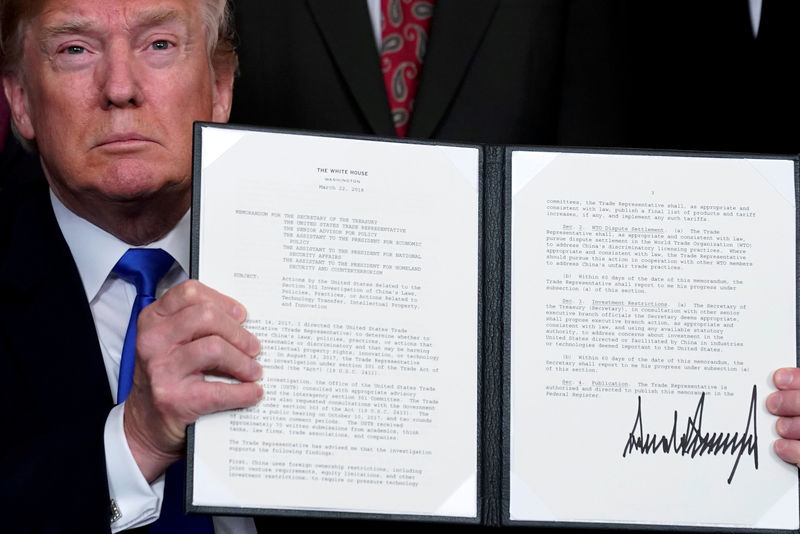

© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: Trump announces intellectual property tariffs on goods from China, at the White House in Washington

© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: Trump announces intellectual property tariffs on goods from China, at the White House in WashingtonBy Tom Miles

GENEVA (Reuters) – President Donald Trump has the World Trade Organization in a chokehold, and the United States has made clear what he wants: no more judicial rulings that interpret WTO rules to Washington’s disadvantage.

Trump has effectively engineered a crisis in the WTO’s system of settling global disputes by vetoing all appointments of judges to its appeals chamber.

True to the president’s style, his ambassador to the Geneva-fbased body, Dennis Shea, is unapologetic about shrinking the supreme court of world trade to a size where it will struggle to function.

“The United States is not content to be complacent about this institution,” Shea told fellow WTO ambassadors this month.

“And the leadership that the United States will bring to the WTO in the coming months and years will consequently involve a good deal of straight talk and a willingness to be disruptive, where necessary, in the interest of contributing to a stronger, more effective, and more politically sustainable organization.”

Trump has proved willing to risk a global trade war in combating any treaties and practices he regards as unfairly disadvantaging U.S. companies and workers, imposing tariffs on steel and aluminum imports globally because of overproduction blamed on China.

Since its creation in 1995, governments have gone to the WTO for adjudication on international trade disputes. Although rulings can be appealed, decisions made judges sitting on its Appellate Body are final, and ultimately sanctions can be used against transgressors.

The rules are far from perfect or complete, and the failure to update them after decades of negotiating stalemate has obliged WTO judges to interpret them for a changing world.

This has incurred Trump’s wrath. “We lose the cases, we don’t have the judges,” he said in February, describing the WTO as “a catastrophe”.

Trade experts dispute this, saying all countries that go to the WTO have a broadly similar rate of winning and losing. While one U.S. judge sits on the Appellate Body, most of the WTO’s 164 members have no representative there, the experts note.

Trump’s veto is reducing what is supposed to be the seven-strong Appellate Body as members’ terms expire. By September four seats will be vacant, leaving three judges, the number required to hear each appeal. If one judge needs to recuse themselves for any legal reason, the system will break down.

Since 1995, the WTO has handled more than 500 disputes and its membership has expanded to cover around 95 percent of world trade, which has more than tripled to around $18 trillion per year in goods alone.

NO TIME-WARP

The Trump administration sees a need to rein in unaccountable judges who overstep their authority. Others, however, see a systemic threat and a desire to return to pre-WTO days when countries settled disputes by negotiation – with the more powerful party usually winning, regardless of the merits of the case – rather than under internationally-agreed rules.

This year Trump has caused an international outcry with the metals tariffs and a $150 billion tariff threat against China for allegedly stealing U.S. intellectual property.

Both moves risk legal entanglement at the WTO.

But disabling the Appellate Body would not simply mean a “time-warp” to an era without judges, according to chief judge Ujal Singh Bhatia. Instead, disputes would go into limbo if the losing side appealed. And with little prospect of enforcing the rules, there would be little point in negotiating new ones.

“The paralysis of the Appellate Body would cast a long and deep shadow on the continued operation of the multilateral trading system as a whole,” Singh Bhatia said.

Eight appeals had been filed since the start of 2017 and more are expected, he said, including a dispute over Australian tobacco control rules which is widely seen as a test case for global health policy.

Shea acknowledged the WTO’s rule book had “substantial value” and had generally contributed to global economic stability. “But something has gone terribly wrong,” he said.

“The Appellate Body not only has rewritten our agreements to impose new substantive rules we members never negotiated or agreed, but has also been ignoring or rewriting the rules governing the dispute settlement system, expanding its own capacity to write and impose new rules.”

A rift opened up when the WTO faulted U.S. methodology for assessing “dumping”, or unfairly priced goods. The consequences for the U.S. ability to tackle what Trump has called China “robbing us blind” were huge.

CLUB FOR THE POWERFUL?

The United States itself also stands accused of rewriting the rules in a dispute brought by Beijing over Washington’s refusal to treat China as a “market economy”.

“Is the WTO really a rules-based organization, or just a club where powerful traditional members can bend the rules?” China asked in a dispute hearing this week.

Although Trump has a pattern of withdrawing from deals he dislikes – such as on curbing climate change and Iran – many WTO diplomats say they remain optimistic that Shea will make proposals to keep the dispute system intact.

Sixty-six WTO members have backed a petition calling for the United States to drop its appointments veto, but there is no agreement on how to avoid the collapse of dispute settlement.

Some countries are discussing using alternative arbitration methods, or having a dispute system which excludes the United States, lawyers and diplomats say.

But U.S. ally Japan is unwilling to join the petition. Ambassador Junichi Ihara said WTO members should refrain from disputes which are “essentially political”.

Japan rejects a dispute system without the United States. “In my view there should not be plan B,” Ihara said. “We have only plan A and we need more collective efforts to find a solution.”

Source: Investing.com