After trying for two years to get a license for a gasoline-powered car in Beijing’s bimonthly lottery, Gary Zhong gave up and bought the Qin EV300 electric vehicle from Warren Buffett-backed BYD Co.

“There was no other way,” said Zhong, 31. “I would have waited forever to get a gasoline-car license, but instead I now find my EV actually works quite well for commuting.”

Zhong exemplifies the early success China is having with its push toward electric vehicles instead of gas guzzlers. While car buyers in China — and everywhere else — still overwhelmingly prefer internal-combustion engines, the country’s carrot-and-stick policies are helping create new opportunities for domestic makers such as BYD and BAIC Motor Corp. and global challengers such as BMW AG and Tesla Inc.

Green license plates for new energy vehicles are displayed in Zhengzhou city in Dec. 2017.

Source: Imaginechina

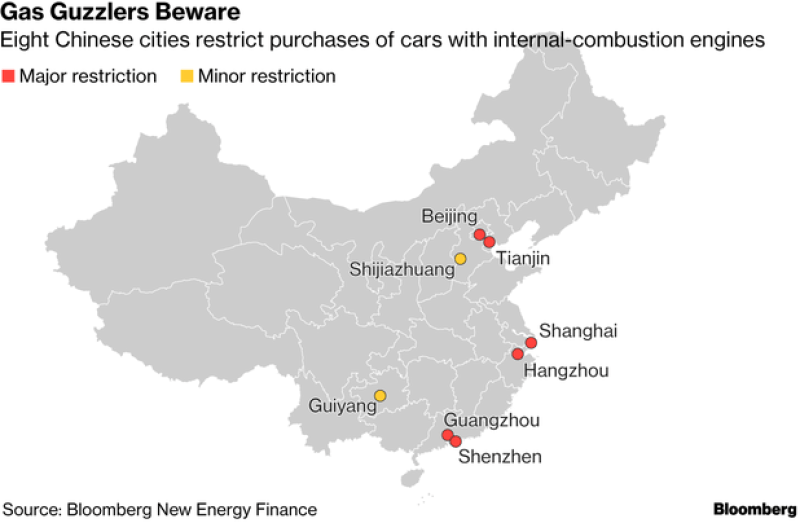

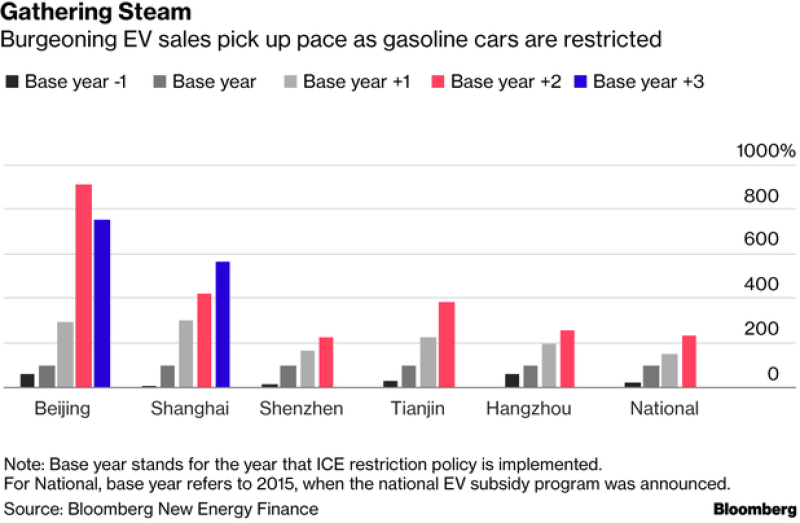

The six Chinese cities that implemented gasoline-car restrictions accounted for 40 percent of the nation’s electric-car sales of 579,000 last year — and 21 percent of the world’s EV sales, according to a report by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Sales in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Tianjin, Hangzhou and Guangzhou are increasing by two to four times the national average, and purchases by individuals versus governments and car-sharing services are at a higher level than elsewhere.

Read a QuickTake on China’s desire to become the Detroit of electric cars

The list price of an electric car — the Qin EV3000 is about $37,000 — often tops that of gas guzzlers in China, yet buying an EV often makes sensewhen considering the difficulties in obtaining an internal-combustion engine vehicle.

“City restrictions have effectively pushed EV sales in China,” said Nannan Kou, a senior associate at BNEF in Beijing who co-wrote the report. “Automakers in China definitely need to prioritize the cities with restrictions in terms of advertisement, sales efforts and government relationships.”

Getting a license plate for a gasoline car can take years through a lottery — held every other month in Beijing starting in February– or cost more than $14,000 in a monthly auction in Shanghai. An EV license is free and often can be obtained a lot faster.

Sales of electric cars still have a ways to go before surpassing those of gasoline vehicles — EVs accounted for about 2 percent of China’s passenger car sales last year, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. By comparison, the global market share is less than 1 percent, BNEF said.

Car buyers at Sanya Notary Office to have their unregistered cars notarized on May 17.

Photographer: Imaginechina

More Chinese cities are set to add restrictions on fossil-fuel vehicles as the country fights air pollution and highway congestion. Hainan island said this month it would limit gasoline-car registrations, and others likely to follow include Nanjing, Foshan, Chengdu and Xi’an, BNEF said.

China is working on a timetable to end the production and sales of internal-combustion vehicles, and it wants electric, plug-in hybrid and fuel-cell vehicles to account for 20 percent of annual new-vehicle sales by 2025.

Shanghai started auctioning license plates in 1994 to control the fleet size in the congested megacity, which last year had 24.2 million residents and 3.59 million vehicles. The price for a gasoline-car permit hit a record 93,500 yuan in October — equivalent to the domestic sticker price of a Volkswagen AG Santana or Ford Motor Co. Escort. The local government has been handing out unlimited EV licenses for free since 2014.

Beijing has run a lottery since 2011, and 2.9 million applicants are competing for 40,000 licenses this year. The use of gasoline cars is further restricted to certain license-plate numbers on certain days of the week.

BYD Qin EV300 hybrid electric car.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Wu Jun, a 28-year-old Beijinger, bought a BAIC EV 200 as the third car for her family after realizing her chances for scoring another gasoline-car license were small. Her parents opposed the idea at first, but now everybody in the family wants to drive the car nicknamed the Xiaobai, she said.

“I never regretted the choice,” Wu said. “It is so convenient to use and so economical. I wouldn’t buy any more gasoline cars.”

Three of her relatives bought EVs after losing the lottery — with some having tried for more than five years.

While EVs help fight pollution, they do little for congestion. That’s why EV sales face a ceiling in China’s biggest cities once the number of vehicles hits limits set by authorities, BNEF said. That effort may be challenged by China’s decision Tuesday to cut the import duty on passenger cars.

Beijing capped the number of EV license plates at 60,000 this year, and there were 218,000 applicants as of February, BNEF said.

A traffic jam at a crossroad in Beijing in April 2018.

Photographer: Fred Dufour/AFP via Getty Images

Zhong, who bought his BYD car in 2016, said some of his friends in Beijing now want an electric car but have to wait for a license.

Lower-tier cities also are trying to boost EV ownership. Liuzhou, in southwestern Guangxi province, allows EVs to drive in bus lanes and provides preferential parking spots.

Qian Weijin, 41, said he drives his tiny two-seat electric car, the Baojun E100 from General Motors Co.’s local joint venture, more than his two gasoline cars because of the perks. About 12,000 new-energy vehicles were sold in the city last year, even without ownership restrictions.

“I can see many people driving these cute, clean and colorful electric cars on Liuzhou streets these days,” said Qian, who has logged more than 3,600 kilometers (2,237 miles) since November. “EVs are actually very convenient.”

— With assistance by Yan Zhang, Ying Tian, Dong Lyu, and Hannah Dormido