(Bloomberg Opinion) — The market is in a coma.

I don’t mean gas prices are low, per se; a market can be in the pits but still jump around like a frog in a sock from day to day. Rather, gas prices appear utterly unresponsive even to defibrillator-like stimuli.

Consider April. Last month was the coldest April in 21 years. With all those boilers staying switched on, the Energy Information Administration estimates, preliminarily, that only 22 billion cubic feet of natural gas made it into storage for next winter – the smallest April injection in 35 years. So gas inventories likely ended the month 27 percent below the seasonal five-year average.

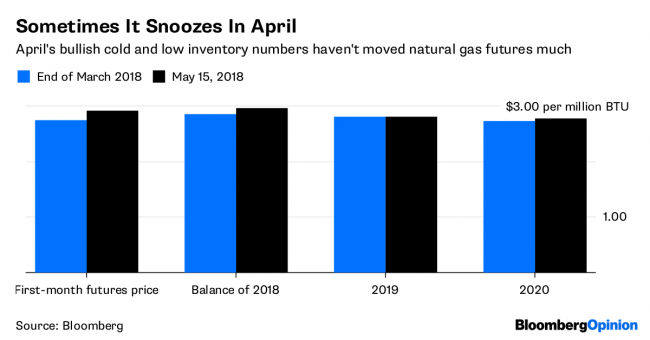

See if you can spot the gas market’s panic:

Looking back to 1999, there have been very few instances of U.S. gas inventories running more than 10 percent below the seasonal average. Right now is one of them:

Again, though, it isn’t merely that absolute pricing is structurally lower. Rather, the relationship between stocks and prices appears to have broken down. Here’s the rolling 52-week correlation coefficient of front-month futures prices and the level of inventories relative to the five-year average:

Prices have fallen along with inventories over the past year . The last time prices marched in such lock-step with inventories was 2004. A crucial factor then was declining U.S. gas production. In November 2003, a consortium including Exxon Mobil Corp (NYSE:). launched plans to build a terminal to import liquefied natural gas to fill a supposedly looming supply gap. So even as gas inventories went up, prices did too, as the U.S. was expected to soon be bidding for more imports to satisfy demand.

One shale boom later, and pending a final investment decision, the Golden Pass facility in Texas should end up mostly exporting LNG.

If the rapid recovery in gas production from shale crushed prices, though, it’s the shale oil boom that’s put them into a coma.

That’s because much of the increase in domestic gas output is a by-product of rising oil production in the Permian shale basin. In a report this week, Sanford C. Bernstein analysts estimate such “associated gas” will be enough to cover roughly two-thirds of the incremental supply needed in the U.S. between 2016 and 2025. Whether or not that gas gets produced is a function of oil prices; low gas prices won’t cause E&P companies to rein in supply as they normally would. As the Bernstein analysts put it: “The U.S. natural gas market is no longer a self-correcting market.”

You can see this in the fact that U.S. gas production is set to hit a new record this year, and then another one next year, even though you have to look all the way out to 2024 before average futures prices crack $3. You can also see it in the way local gas prices in the Permian basin have disconnected from the national benchmark – a coma within the market’s coma:

Absent a reversal in Permian oil production – which seems unlikely, even with near-term pipeline bottlenecks – the gas market’s comatose condition looks set to continue.

That’s an unalloyed problem for those E&P companies mostly tied to gas. Growing output into a market already gorged senseless sounds more like masochism than an equity pitch. And while the odd cold snap or heatwave can spark a temporary rally in prices, equities discount the deadening impact of the wider glut more heavily, as January showed:

On the other hand, it’s great for U.S. consumers, for whom low gas prices help to mitigate increases in heating and electricity bills.

A comatose market is also good for those with the infrastructure to ship gas to market or, even better, offshore. Similar to how refiners capitalized on the old U.S. crude-oil export ban or, more recently, Permian bottlenecks causing dislocations in that market, pipeline owners more concerned with volume than price can benefit from the gas glut (a bright spot amid the turmoil around master limited partnerships.) And for LNG exporters with access to existing and approved projects, such as Cheniere Energy Inc., cheap gas just boosts business and margins.

At some point, a slowdown in Permian oil production could provide the correction needed in gas supply (though don’t forget the monster in Appalachia). Moreover, the whole energy dominance thing should result in more LNG export terminals providing a jolt as gas finds an outlet to higher prices overseas. Planning, permitting and building them will still take years, though. This patient won’t be awake for a while yet.

Source: Investing.com