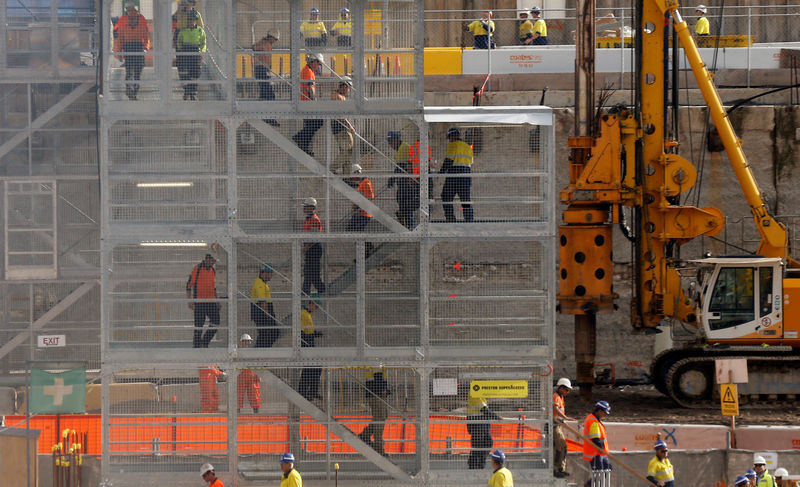

© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: Construction workers descend using temporary stairs on a major construction site in central Sydney

© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: Construction workers descend using temporary stairs on a major construction site in central SydneyBy Swati Pandey

SYDNEY (Reuters) – After a record 26 years of uninterrupted economic growth, Australian workers should be sitting pretty. They aren’t.

Their annual wage increases are, by some measures, lagging inflation, job security is an issue, and at least one survey shows their sense of overall wellbeing is at an all-time low.

Many policymakers and mainstream bank economists puzzle over the reasons for all this.

They point to Australia’s transition to more of a services economy, the impact of disruptive technologies, the lack of productivity growth, and the increase in the number of part-time and temporary jobs as among reasons.

But some labor experts have a better explanation: a plunge in trade union membership in Australia to less than 15 percent of the workforce now from more than 40 percent in 1991, much greater than declines in other industrialized countries.

They say that has allowed employers to dictate the size of wage rises without challenge.

“Unionization has collapsed far more violently in Australia than virtually anywhere in other developed, rich countries,” said Josh Bornstein, Melbourne-based employment lawyer at Maurice Blackburn, who often represents workers in litigation.

“Unions have been disempowered and that is bad for wage outcomes,” he added.

The contrast between stellar growth – the nation’s economy expanded at a 3.1 percent annual rate last quarter to outpace the United States, Europe and Japan – and the lot of ordinary Australians is a major concern for policymakers.

It poses a big political challenge for Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull who has been flagging in polls for more than two years now, and who will probably hold a general election by next May.

Average annual compensation per employee crawled up by 1.6 percent last quarter, below the inflation rate of 1.9 percent, as companies took a large slice of the income pie with operating profits surging to a record. A separate measure released in May showed the wage price index, which follows price changes in a fixed basket of jobs, rose 2.1 percent last quarter.

To be sure, low wage growth is a global phenomenon but it was exacerbated in the United States and Europe by big job losses in the 2008/09 financial crisis. By contrast, on the back of commodities demand from China, Australia grew through that period.

The weak wages growth could eventually undermine an economy that has done better than those of just about every other major nation in the western world over the past quarter century.

Household spending contributes 57 percent of Australia’s GDP, and if people are feeling squeezed then it won’t take much for them to postpone that purchase of a big ticket item, such as a washing machine or car, hurting retailers, distributors and manufacturers.

Philip Lowe, the governor of the nation’s central bank – the Reserve Bank of Australia – says structural changes in the labor market driven by technology disruption, leading to the rise of the so called gig or sharing economy and increasing numbers of part-time and casual jobs – may be critical factors.

Australia’s labor productivity has not been improving either, he noted in a speech last week.

But even Lowe says he is perplexed about the causes of low wage growth in economies like the United States where the jobless rate has tumbled.

(GRAPHIC: Australia’s wage growth slumps even as economy revives – https://reut.rs/2Lxh10J)

LOST THEIR MOJO

While the labor unions have also lost their mojo in other major industrialized countries, the extent of the fall is much worse in Australia. In Britain, for example, union membership sits at about 23 percent of the workforce now, down from 37 percent in 1991.

A report jointly produced last month by Credit Suisse (SIX:) and the University of Queensland’s Australian Institute for Business and Economics suggested that unionization and wage growth go hand in hand.

“Collective wage agreements, organized on behalf of union members, have delivered increases in wages ahead of the non-unionized employees,” according to the study.

For instance, from 1998 to 2008 collective wage agreements averaged an annual increase of almost 4 percent while the total labor market only managed 3.6 percent. The spread was even larger for the next ten years when the unionized workforce gained 3.4 percent versus 2.9 percent for the total pool.

Australian union membership has been plunging because of the demise of traditional manufacturing industries that were heavily unionized, and labor market deregulation in the 1990s which decentralized wage setting and reduced the powers of unions.

In addition, the millennial generation unlike some of their parents has not grown up in an atmosphere where joining a union was regarded as one of the rites of passage, and many newer employers actively campaign to prevent unions from getting a foot in the door.

Still, some economists think the impact of weaker unions on pay is modest.

Alicia Garcia Herrero, Hong Kong-based regional economist for French investment bank Natixis, says unions are more focused on retaining jobs than raising wages because of the hollowing out of key industries.

(GRAPHIC: Australia jobs growth strong, unemployment still high – https://reut.rs/2JBHsVH)

TALES OF HARDSHIP

It is easy to find stories of Australians struggling with high levels of debt and finding it difficult to eke out a living.

Indeed, the share of national income going to employees is near the smallest since 1960 at about 47 percent, down from 56 percent at the end of last recession of 1991. The share going to companies has climbed to almost 27 percent from about 21 percent.

In one sign that Australians are not sharing in the economic success, a measure of wellbeing skidded to a record low last quarter, a survey of over 2,000 residents by the National Australia Bank showed earlier this month.

The index is based on responses to questions such as how satisfied are you with your life nowadays and how happy did you feel yesterday.

The Reserve Bank’s Lowe recently said that workers are worried and therefore less likely to make a fuss about low-ball wage deals.

“Workers feel like there are competitors out there, they’re worried about the foreigners and the robots,” he said in a reference to the flow of migrants into the country.

“And, when any of us feel that there is more competition you’re less inclined to put your price up.”

Source: Investing.com