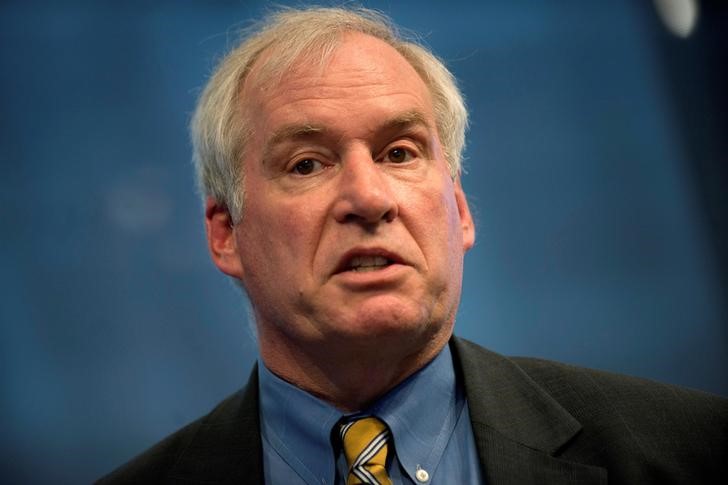

© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: File Photo: The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s President and CEO Eric S. Rosengren speaks in New York

© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: File Photo: The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s President and CEO Eric S. Rosengren speaks in New YorkBOSTON (Reuters) – The tight U.S. labor market may be good for workers, allowing them to jump between jobs more easily and coax higher wages from their boss.

But it may also pitch the economy toward unexpected inflation or other problems if it remains as low as the Federal Reserve anticipates, Boston Federal Reserve president Eric Rosengren said on Monday in remarks defending the case for continued interest rate increases by the Federal Reserve.

The Fed’s most recent projections show the unemployment rate hovering between 3.5 and 3.7 percent for more than 3 years, nearly a full percentage point below what Fed officials regard as sustainable in the long run without a run-up in wages and prices.

“The further we get from full employment the further risk there is,” Rosengren said in remarks at a meeting of the National Association for Business Economics. “While inflation remains well contained to date, pushing the economy too hard risks inflationary concerns or financial-stability risks. Either of these outcomes might necessitate a more forceful monetary policy response.”

Financial sector problems could also develop, he said. While there are no “alarm going off” at present, Rosengren said, “there are a bunch of yellow lights,” including a commercial real estate boom that may have raised prices beyond what market demand can sustain.

Rosengren spoke at a time when the Fed is trying to navigate how best to keep the current recovery underway, allowing workers and families to potentially make up some of the ground lost over more than a decade of weak wage growth, while also guarding against broader inflation or other problems that could set the stage for a fresh downturn.

While the traditional link between unemployment and inflation has been weak in recent years, many at the Fed regard it as dangerous to assume the U.S. can sustain what would be a historic run of low joblessness without rising prices associated with higher wages, more spending power, and more competition for goods and services.

In addition, there is also a sense among forecasters that, eventually, a downturn will develop.

Among 51 economic forecasters surveyed before the conference, nearly 90 percent expect a recession before the end of 2021, and more than half by the end of 2020 – a contrast with Fed projections that see an epoch of steady growth and low unemployment ahead.

With rising global tariffs potentially also leading to higher prices, wage hikes starting to accelerate, and employers struggling to fill jobs, Rosengren argued that the Fed should continue raising rates “until monetary policy becomes mildly restrictive.”

That may gradually slow the pace of hiring and the economy. But it could also guard against more serious problems, Rosengren said, keeping the Fed near its twin goals of “stable prices and maximum sustainable growth.”

As it increased rates last week, the Fed indicated it would continue tightening to around 3.4 percent by sometime in 2020, a slightly restrictive level.

Fusion Media or anyone involved with Fusion Media will not accept any liability for loss or damage as a result of reliance on the information including data, quotes, charts and buy/sell signals contained within this website. Please be fully informed regarding the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, it is one of the riskiest investment forms possible.

Source: Investing.com