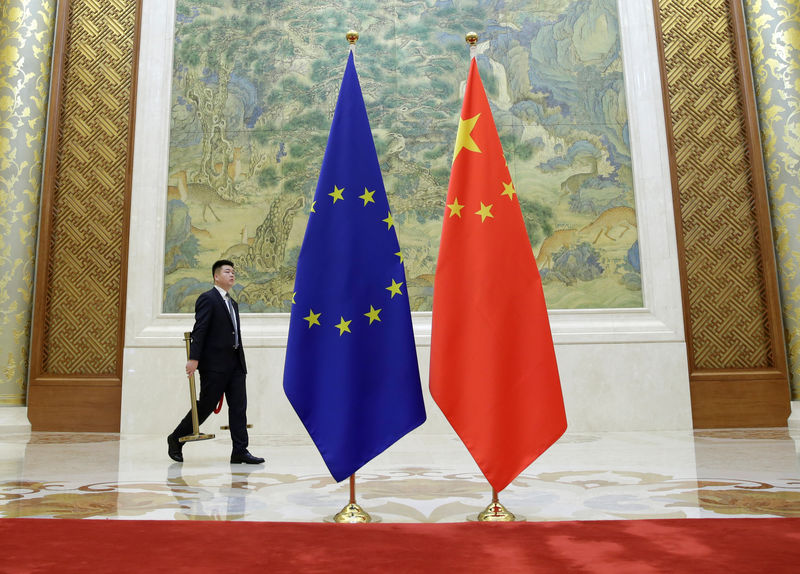

© Reuters. A staff member prepares for the EU-China High-level Economic Dialogue in Beijing

© Reuters. A staff member prepares for the EU-China High-level Economic Dialogue in BeijingBy Philip Blenkinsop

BRUSSELS (Reuters) – The European Union on Tuesday provisionally agreed on rules for a far-reaching system to coordinate scrutiny of foreign investments into Europe, notably from China, to end what a negotiator called “European naivety”.

Negotiators for the European Parliament and the EU’s 28 member states struck a deal to protect strategic technologies and infrastructure, such as ports or energy networks.

Under the plan, developed in the wake of a surge in Chinese investments, the European Commission would investigate foreign investments in critical sectors and offer opinions.

The opinions could address concerns over whether the security of vital infrastructure could be compromised or that innovations that have had years of expensive research could be lost to foreign hands.

“It will mark the end of European naivety,” Franck Proust, who headed the parliament’s negotiating team, said ahead of the talks. “All the world powers – the United States, Japan, China, – have a method of screening. Only Europe does not.”

The proposed new law does not name China, but its backers’ complaints over investments by state-owned enterprises and for technology transfers are clear references to Beijing.

The proposal, demanded by France, Germany and the previous government of Italy, still needs the support of the 28 EU states at a meeting on Dec. 5. Their backing is by no means certain given opposition from a number a countries, including Cyprus, Greece, Luxembourg, Malta and Portugal.

Some of the opponents have welcomed Chinese investment, such as Greece, whose largest port Piraeus is majority-owned by China’s COSCO Shipping.

“This is not about closing down our markets but about acting responsibly,” said Austrian Economy Minister Margarete Schramboeck, whose country represented the EU states and urged them to back the compromise text.

Parliament will vote on the proposal in February or March.

EU lawmakers succeeded in pushing through tougher screening than initially proposed, such as obliging the Commission to screen deals and requiring EU countries to cooperate.

They also extended the list of “critical sectors” to include aerospace, health, nano-technology, the media, electric batteries and the supply of food.

The system would not require individual countries to carry out screening. Currently 13 nations have a system in place. Those that do will need to inform other EU members and the Commission if they screen an investment.

All would have to provide an annual report to the Commission, which would also be obliged to give its opinion if a third of member states expressed concerns about a planned foreign investment.

However, EU countries, and not the Commission, would still make final decisions on whether to block foreign investments on security and public interest grounds.

Source: Investing.com