© Investing.com

By Geoffrey Smith

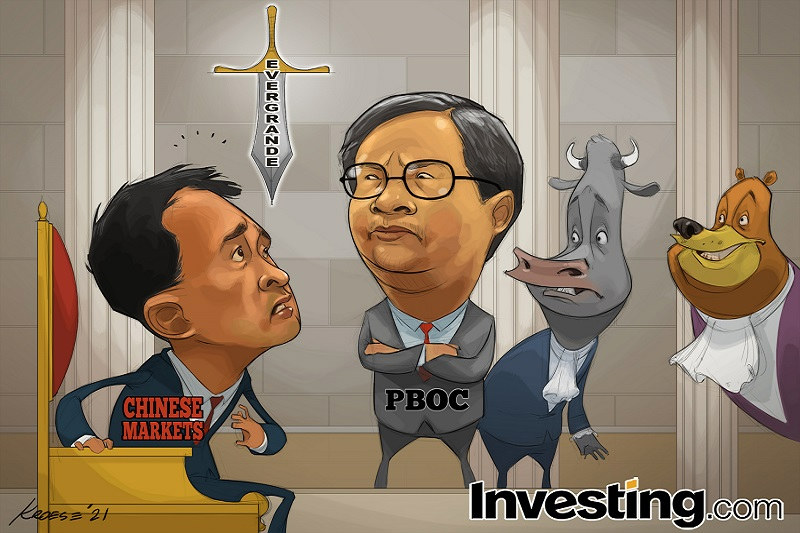

Investing.com — According to legend, King Dionysius of Syracuse – tired of the flattery of his courtier Damocles – had a sword suspended by a single thread of horsehair above Damocles’ head, to teach him how precarious the privileges of power and wealth were.

Today, investors in Chinese assets are learning the same lesson at the hands of the Beijing government and the People’s Bank of China, and the sword hanging above their heads bears the name ‘Evergrande’.

Like Dionysius, President Xi Jinping is trying to teach someone a lesson. In this case, the lesson is that the days of reckless, unsustainable borrowing that have sustained China’s suspicious-looking growth figures for a decade – are over (we won’t say whose arbitrary growth targets that borrowing was intended to meet).

As Columbia University professor Adam Tooze puts it, this is why China Evergrande Group (OTC:EGRNY) is unlikely to go down in history as “China’s Lehman Brothers.”

“Unlike the disastrous chain reaction at Lehman, this is a controlled demolition, deliberately triggered by the regime.” Tooze explained in a blog post last week. “Beijing is doing what critics have been asking China to do for a while – to deflate the housing bubble. It is doing what the West did not do in 2007-2008, i.e use regulatory intervention to manage a hard landing short of outright crash.”

That the bubble needs deflating is not in question. According to data compiled by E-House China Enterprise Holdings, average house prices in Shenzhen are over 43 times average incomes, while in Beijing, the multiple is over 41. For comparison, New York and London, which are bywords for real estate markets that are detached from reality, have multiples of 10 and 15.

The question is – how do you deflate a bubble of that size without crashing the broader economy? Real estate sales account for about one-third of local government revenue. Annual investment in real estate is twice as high in absolute terms as in the U.S., and its share of GDP is around three times as large – 13%, compared to less than 5% in the U.S. (according to Commerce Department figures for 2018). It accounts for one in six jobs in China’s teeming cities.

Even in the kind of benign scenario trickling out via newswire reports, in which the authorities use their ample leverage over a state-dominated domestic financial system to agree on sharing the burden of Evergrande’s $309 billion in debts, the reality is that a lot of them will not be paid. Given Beijing’s natural desire to ensure that trade payables are settled first, and that those who have paid in advance for houses actually get them, it seems likely that financial creditors – bondholders and bank lenders – will bear most of the losses.

A more uncertain question is how much pain Beijing is willing to impose on individual investors who bought high-yielding and barely regulated “wealth management’ products from the company. The popularity of such instruments across the country means that a severe haircut on them could trigger retail investor panic.

Given the scale of the losses, the variety of the creditors, the importance of land sales for local government budgets (especially in China’s tier 2 and tier 3 cities where Evergrande was the biggest buyer), the risk is that even a consensual resolution of its debts ends up having unintended consequences. In other words, even if the lesson is absorbed the way Beijing wants it, the authorities will still struggle to contain the fallout.

“For three decades, Chinese lenders have made loans based on the assumption that large borrowers would be bailed out,” Michael Pettis, a professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University, wrote last week. “To erase the assumption of moral hazard would mean wiping out the structural underpinnings of the country’s credit markets.”

That means higher interest rates and weaker demand from the most systemically important source of growth in the last decade, until the new rules of the game – who should get access to credit? And what guarantee of repayment will there be? – are clear. That might take months, or even years.

Evergrande is not the only developer that will need resolving, and even the government’s resources are not infinite. A broad slowdown – with all that implies in terms of domestic social stability and for the broader world economy which lives from Chinese commodity demand – is inevitable.

Source: Investing.com