Bond market behavior last week was somewhat disturbing as 10-year nominal rates shot past 4% and 10-year real rates got as high as 1.75% before pulling back a trifle. This was despite Fed speakers starting to soften the message, signaling that there is probably a taper coming soon in the rate of tightening.

Early in the week, investors roundly misinterpreted comments by Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari. He remarked that if core inflation continued to surprise on the high side, he thought it would be appropriate to continue tightening. Bonds took this very poorly. But it is actually a cheerful message and a pivot to a more-dovish perspective (admittedly, from one of the Fed officials whose dove/hawk score swings wildly depending on the day).

Previously, Fed speakers had generally indicated that they wanted (and expected) to see inflation decelerate significantly before they would pull off the ball. Chairman Powell infamously intoned back in March that the Fed would keep tightening “until the job is done.” It’s hard to say the job is definitively “done” until inflation is demonstrably in retreat, but Kashkari didn’t demand that. All he asks is for core inflation to stop surprising on the upside. Heck, in theory, that could even happen with inflation continuing to rise, as long as economists finally catch up to what is happening and raise their expectations by more. But I think what he meant was just that he’d like to see a clear cessation in the pattern of continued new highs! As I noted in my monthly CPI analysis, Median CPI has increased year on year (yoy) for the last 14 consecutive months. It will probably peak in December, right on schedule for a downshift from the Fed.

The shift in message from wanting to see a clear movement lower to instead wanting to just see a cessation of surprising new highs is very significant and likely signals that—if the numbers over the next few months don’t accelerate further—the Fed is probably on a 75 basis points (bp), 50bp, 25bp trajectory over the next few meetings. On Friday, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said policymakers should be thinking about reducing the size of rate hikes: “we might find ourselves, and the markets have certainly priced this in, with another 75 bp increase, but I would really recommend people don’t take that away as, it’s 75 forever.” She opined that 50bp or 25bp would make more sense as the Fed gets closer to the end. St. Louis Fed James Bullard sang the same tune:

“Once you’re at the right level, then you can just make minor adjustments at that point. Maybe to stay where you are, maybe to go a little bit higher, based on incoming data.”

These are messages of a turn towards gradualism as the Fed reaches what they think is a terminal rate. Since inflation is a lagging indicator (as Daly said the prior week), the Fed should not wait until inflation is sharply in retreat before pausing…and that’s what Kashkari said.

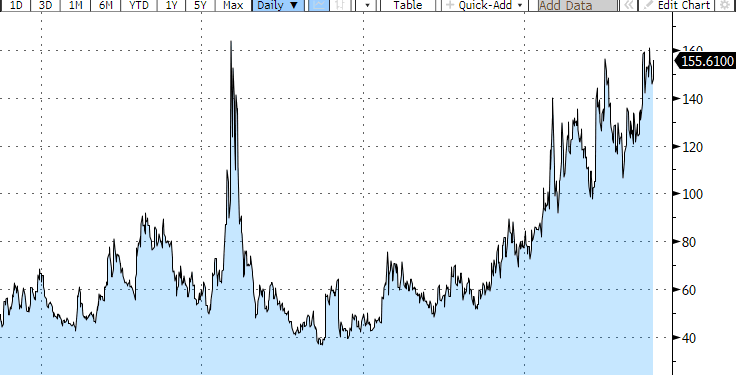

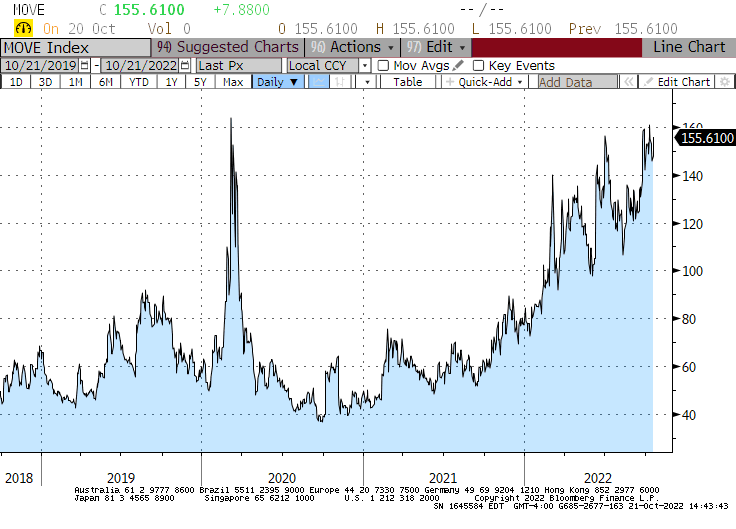

They all are aware that they’d rather pause or cease tightening because they choose to, and not because something broke in the markets. But the continued rise in long-term rates, and the disturbing continuing rise in implied volatilities (see chart of the MOVE index, a measure of bond market volatilities) despite the Fed’s moderating message, is an early warning. As we head into the last two months of 2022, we are probably closer to a liquidity accident than we’d like to think.

MOVE Index

MOVE Index

Source: Bloomberg

Taking a Step Back…

Investors should keep reminding themselves that the Fed has a tool to impact price and a tool to impact economic output, but they are not the same tool.

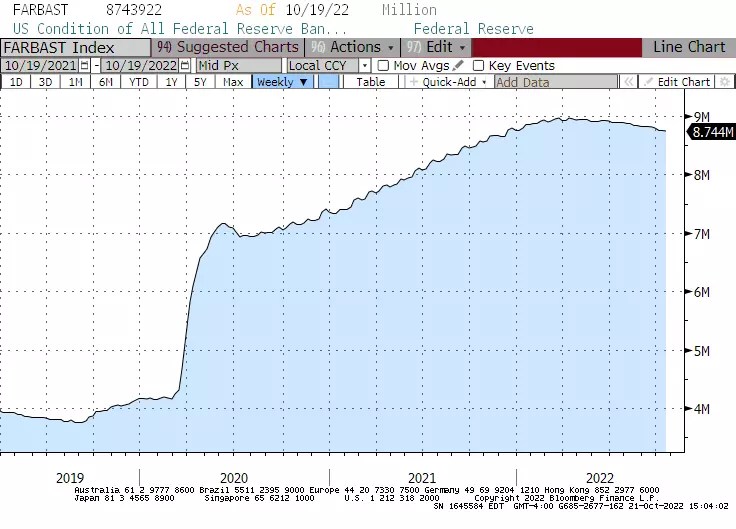

The Fed’s tool to impact price is the level of reserves, by which they traditionally have influenced the growth rate of money. The quantity of money is the single largest determinant of the level of prices in the economy. Presently, the Fed is shrinking the quantity of reserves by shrinking the balance sheet very slowly, as the chart below shows. As I’ve mentioned before, though, banks are not presently reserve-constrained so this very small balance-sheet runoff is not having a big effect on price. However, at least the direction is correct.

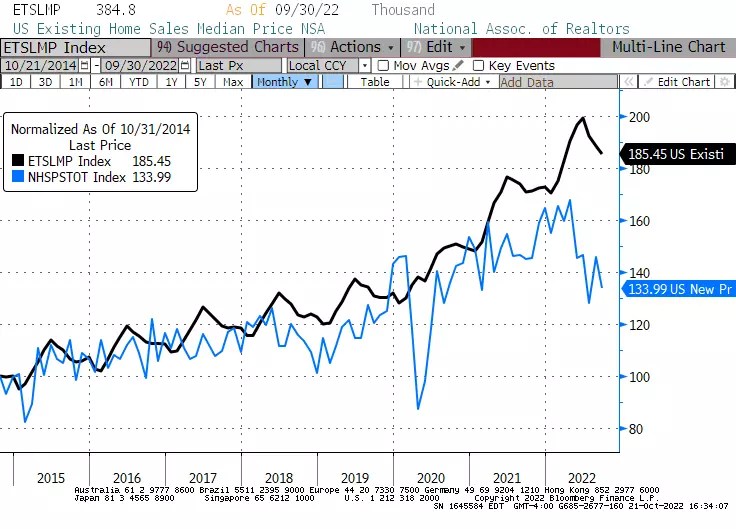

The Fed’s main tool to impact output is interest rates. Now, it used to be the case that these two tools were one single tool and the Fed manipulated reserves to influence interest rates. They are now separate tools, and the important thing to remember is that the interest rate tool predominantly affects output by raising the nominal cost of capital to businesses and individuals. (It also affects the returns of levered investors in a much more direct and serious way, but that’s not the Fed’s fault). Drastically increasing risk-free rates will slow economic growth. It’s already slowing the activity in the housing market—starts and sales—although not prices. The chart shows (indexed to late 2014) the rate of housing starts (in blue), and the median price of existing homes (in black). Note that existing home sales prices are noticeably seasonal; the decline in price over the last couple of months is roughly seasonally normal.

US Fed Balance Sheet

US Fed Balance Sheet

Source: Bloomberg

This is just one sector, but it is one that is very sensitive to monetary policy. The effect you see—higher interest rates affecting output, but not prices—is what you should expect to see going forward across various economic sectors.

Existing Home Sales Median Price

Existing Home Sales Median Price

Disclosure: My company and/or funds and accounts we manage have positions in inflation-indexed bonds and various commodity and financial futures products and ETFs, that may be mentioned from time to time in this column.

Source: Investing.com